How metalheads revived the Sundanese jaw harp karinding - PART 1

Presentation given at the International Society for Metal Music Studies conference in Seville, June 2025

I recently travelled to Seville, Spain, to give a presentation at the International Society for Metal Music Studies (ISMMS) conference. I was there to share material from a chapter from my co-authored book with Owen Coggins about jaw harps and heavy metal. We’ve been working on this collaborative project for several years now, combining our expertise to explore the phenomenon of jaw harps being embraced by metal musicians around the world. The book traces the instrument’s journey through the metal world from the UK (where it appears on the first Black Sabbath album), to the USA, Scandinavia, Latin America, Indonesia, Central Asia, and finally back to Europe. Today, I’m giving you a summary of the presentation I gave about the karinding revival in Bandung, West Java at ISMMS in June 2025. The presentation text appears under each slide.

This presentation is based on a chapter from a book project about the global phenomenon of jaw harps being used in metal music, co-authored with Owen Coggins and contracted with Routledge/Ashgate

It’s been in development since 2020. In 2022, we co-taught a seminar on it at VCC and we presented an overview at the ISMMS conference in Mexico City. Today’s presentation is our first time presenting on a single chapter in detail.

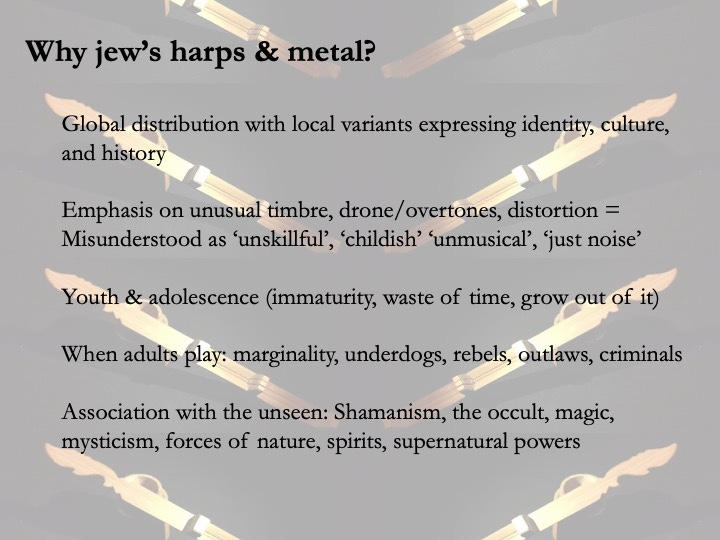

But first, let’s revisit some of the main themes and associations that make jaw harps and metal a particularly rich intersection to explore. It’s worth pointing out that these associations are not consistent in every single jaw harp tradition, but they are frequently seen in our particular case studies

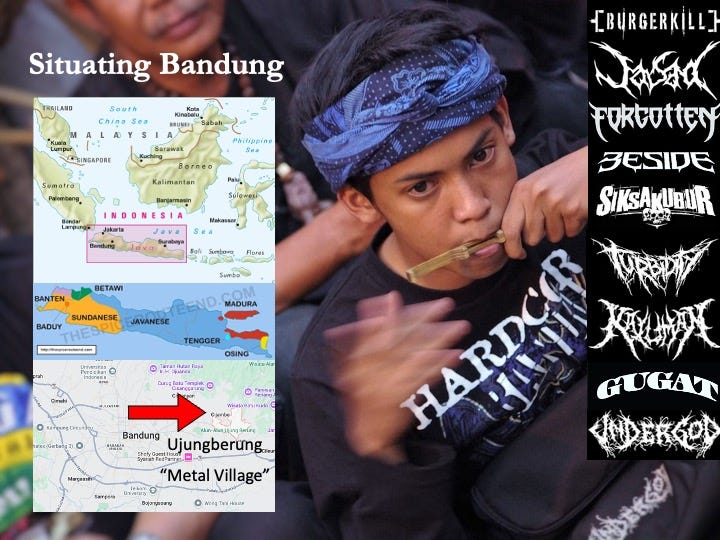

Bandung, West Java is one of the largest metal scenes in the world.

The term “Sundanese” refers to the ethno-linguistic group which is dominant in this region of the island (shown on the second map in orange). Ujungberung district on the northeastern side of Bandung city is dubbed locally as “Metal Village”, and is regarded by many as the birthplace of the Indonesian metal scene.The “Ujungberung Rebels” community has produced hundreds of bands and a vibrant underground scene since the 1980s comprised of independent recording studios, cassette trading, amateur radio, zines, and metal festivals.

Indonesia’s unofficial “Big Four” metal bands are notably ALL from Bandung: Burgerkill, Jasad, Forgotten, and Beside. Other well-known Bandung bands include: Siksakubur, Turbidity, Kaluman, Gugat, Undergod, and many, many others.

This photo encapsulates the themes of today’s presentation: how traditional and metal signifiers coexist in Bandung and articulate a Sundanese modernity that is both hyperlocal and cosmopolitan. Today I’ll be discussing how the Sundanese karinding revival occupies a special place in global metal: it is the only case study in our book, and to our knowledge, in which a jaw harp revival has emerged from an underground metal scene.

So, how did we get here?

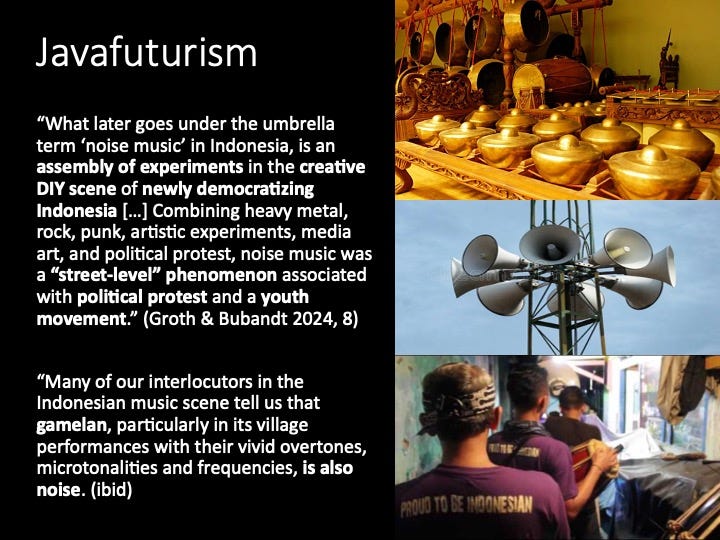

I want to start by using Groth & Bubandt’s term “Javafuturism” to problematize applying the Western concept of “noise” to music in Indonesia. Whereas “noise” music in the West was conceived as an explicit break from the conventions of homophonic harmony, tonality, and form, […] In Indonesia, the texture of court music in Java and Bali in particular was characterized, not by linear melody, but by heterophonic texture and microtonality. (Groth and Bubandt 2024, 7)

So, in a place where cyclical layers of texture and timbre and relative pitch centres reign supreme over harmony, linearity, and standardized pitch, what does noise even mean? What is noise aesthetics in a place where everything is “noisy”?

Groth and Bubandt argue that in Java, noise is not a discreet genre:

“What later goes under the umbrella term “noise music” in Indonesia, is an assembly of experiments in the creative DIY scene of newly democratizing Indonesia […] Combining heavy metal, rock, punk, artistic experiments, media art, and political protest, noise music was a “street-level” phenomenon associated with political protest and a youth movement rather than a rarified artistic genre.” (ibid, 8)

Further, they point out that many Indonesian noise music artists told them that: “gamelan, particularly in its village performances with their vivid overtones, microtonalities and frequencies, is also noise.” (ibid, 8)

So there is a sonic pre-disposition here that has contributed to the largescale embrace of heavily distorted genres like metal. But again, the concept of "distortion" in this context falls short, as it implies the ruination of a pure signal, rather than an aesthetic preference for timbre, texture, and overtones. In other words, what is considered noisy and oppositional to the West, may actually just fit right in on Java, with metal arriving not as a foreign export or harbinger of cultural imperialism, but as something already somehow deeply familiar, relevant, and engrained.

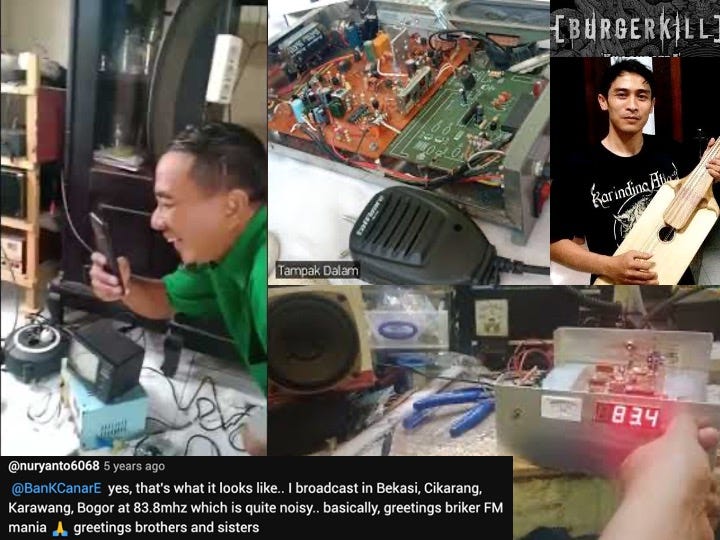

We also see this aesthetic in the DIY amateur radio scene, which was a beloved hobby of 80s and 90s Indonesian youth before the era of cellphones, and played a direct role in the development of the underground metal scene in Bandung.

Brik-brikan radio, literally “crackle” or “noise” radio, refers to the DIY FM transmitters that was hugely popular in and around Bandung. The Sundanese term “Ngebrik” literally means making noise or making a fuss, and the radios, with their resolutely exposed circuitboards are still referred to as Brik FM, literally “noise FM”.

What is incredible is that several of the first generation metalheads who would go on to form the Ujungberung Rebels community actually bonded through this hobby. As a blog post by Obozs reports: “Dinan (Necromancy) first met Uwo-Agus (Funeral) from jamming brik-brikan. [...] The members of Monster were brik-brikan addicts. They talked about music, exchanged information, and finally met, formed a band, and built a community.”

Kimung, top right, was a founding member of Monster, the original bassist for Burgerkill, and a founder of Karinding Attack, who I’ll discuss shortly. He is now a historian of the Bandung metal scene and a karinding activist and educator.

In interview, he told me that he and his friends had a schoolteacher who taught them how to make their own radios, and recalled running cables to antennas outside their bedroom windows and finding ways to jam the button down on the CB microphone so that it could be placed in front of the speaker of a cassette player, and used to broadcast the latest tapes to each other over the air.

Now, a huge amount of additional noise and distortion was introduced to the music through this sharing process: the white noise of the radio medium itself was enhanced by the fact that they were usually broadcasting over the lowest frequencies on the FM dial that were not being used by commercial stations because the reception was so poor (the low 80s). However, this was not an impediment to the youth at all—quite the opposite, the distortion was prized as being fun and part of the experience.

Kimung recalled hearing Sonic Youth for the first time over Brik radio, and thinking that it was an extreme noise band. When he finally heard the clean studio recording, he said, “oh THAT’s what they sound like?” So Brik radio basically made everything sound more metal, including metal and things that weren’t metal!

Amazingly, these distorted pirate broadcasts came to the attention of the owners of the local private radio station, and according to Kimung were part of the impetus to turn it into the first dedicated rock music station in Indonesia. These broadcasts were part of a body of evidence, along with zines, bootleg cassettes, and underground venues, that heavy music was something Bandung wanted to hear.

It’s in this sonic environment that Sepultura enters the chat.

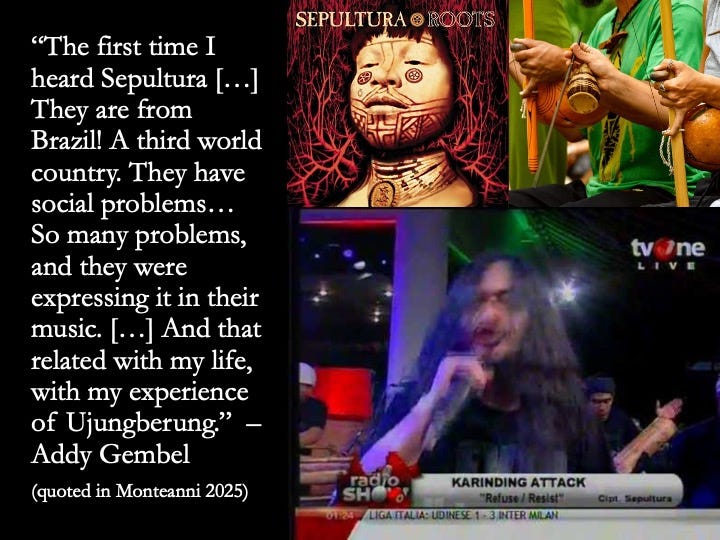

In the 1980s & 90s, Thrash metal was a huge influence on the first generation of Bandung metal bands, several of which actually started as Sepultura cover bands before moving on to write their own material. Bandung bands related to Sepultura not just sonically but thematically with regards to indigeneity and post-colonial experiences of identity reconstruction.

Luigi Monteanni (2025) quotes Addy Gembel from Forgotten: “The first time I heard Sepultura […] They are from Brazil! A third world country. They have social problems… So many problems, and they were expressing it in their music. […] And that related with my life, with my experience of Ujungberung.”

Sepultura’s 1996 Roots album was particularly influential. First, it employed the use of the berimbau, an Afrodiasporic musical bow that has become an emblem of Brazilian national identity through the mid-twentieth resurgence of capoeira. Interestingly, it produces a similar buzzing timbre to a jaw harp and has been frequently mistaken for one by listeners over the album’s 3-decade history. Sepultura's use of a berimbau on the album resulted in a surge of interest in the instrument both at home and abroad, as well as an interest in incorporating traditional instruments into metal in general.

By the early 2000s, the second and third generations of Bandung metal bands were well established and some were already starting to collaborate with local traditions.

Karinding Attack appeared on the scene in 2008, taking these developments quite a few steps further with a sound they called “heavy bamboo” or “bamboo-core”. Founded by Kimung from Monster and Burgerkill and lead singer Man from Jasad, the group started a trend in Bandung and dozens of similar bands were formed over the next several years.

This post is continued in Part 2 below!

Works Cited

Bithell, Caroline, and Juniper Hill, eds. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Groth, S. K., & Bubandt, N. (2024). Noise Without Noise: Art Interventions in a Southeast Asian City. In InterNoise 2024: Proceedings of the 53rd International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering: 1-11.

Kimung. 2019. Sejarah Karinding Priangan. Minor Books.

Kimung. 2022. The Dynamics of Karinding in West Java. Journal of the International Jew’s Harp Society 7: 22-33.

Monteanni, Luigi. 2025. “Extreme Traditions: On Bandung’s Intergenerational Sonic Ecologies.” CTM Festival Magazine. https://www.ctm-festival.de/magazine/extreme-traditions-on-bandungs-inter-generational-sonic-ecologies.

Monteanni, Luigi. 2025. “Extreme Traditions: On Bandung’s Intergenerational Sonic Ecologies.” CTM Festival Magazine. https://www.ctm-festival.de/magazine/extreme-traditions-on-bandungs-inter-generational-sonic-ecologies.

Spiller, Henry. 2023. Archaic Instruments in Modern West Java: Bamboo Murmurs. SOAS Studies in Music. New York: Routledge, 2023.

I’m looking up all of these bands now.

Fascinating!! Can’t wait for the second part of the journey!