How metalheads revived the Sundanese jaw harp karinding - PART 2

The second part of the presentation given at the International Society for Metal Music Studies conference in Seville, June 2025

This is the second part of a two-part series where I share the presentation I gave about the karinding revival in Bandung, West Java, at the recent International Society for Metal Music Studies (ISMMS) conference in Seville, Spain.

You can read the first part of the presentation here:

Today’s instalment goes into greater detail about the formation of Karinding Attack, the influential band that kicked off the “heavy bamboo” movement in Bandung, as well as the philosophies underpinning these events. I hope you enjoy the second half, and please let me know what you think!

I’ve explained some of the forces that led to the formation of this unique project. But we have to dig a bit deeper into how and why Karinding Attack was formed.

The band was founded as a direct response to the AACC Tragedy on Feb 9, 2008, which happened at an album launch for Beside at the Asia Afrika Culture Centre in Bandung. After the show, a combination of overcrowding, dehydration, and panic resulted in a stampede when the crowd tried to exit the venue. This led to 11 fatalities among the youth who were present, and many more injured.

This was a watershed moment for the Bandung scene: metal shows were temporarily banned, and the community went into mourning and did a lot of soul searching during this time. As Henry Spiller puts it in his recent chapter about karinding, the tragedy was seen as “un-Sundanese”, and this precipitated a journey among members of the Ujungberung Rebels to reconnect with Sundanese values as part of a healing process (Spiller 2023, 101).

Kimung began travelling to villages throughout West Java, speaking with elders about Sundanese traditions. It was through this process that he seized on karinding as emblematic of fundamental Sundanese values. He brought elder karinding maker and player Abah Olot to Bandung to give workshops. Olot comes from a family lineage of karinding makers who recall the instrument being played during village ceremonies going back several generations. These include thanksgiving celebrations as well as ceremonies for eclipses and full moons (Suwandi 2013, 28; Art Etsa Logam 2013, quoted in Spiller 2023, 94), connecting it with a pre-colonial agrarian way of life.

To say the instrument's introduction in Bandung resonated is an understatement. Things moved quickly, people were inspired, and by the end of the year, Karinding Attack had been formed, with many recognizable musicians joining its ranked from the first generation of Ujungberung Rebels.

So, why the karinding?

Jaw harps are all over Indonesia: Palmer Keen of Aural Archipelago has recorded at least 15 living jaw harp traditions, and that’s not counting the ones that have gone extinct or are still being practiced in under the radar.

These traditions are hyperlocal: travel a couple of hours in any direction, and the instrument is called something else (rinding, kurinding) and is built and played and conceived of differently.

Karinding is old. We don’t know exactly how old, but at least several hundred years, likely much older. Because it’s made of bamboo, it doesn’t leave a trace.

According to Kimung’s interviews with hundreds of villagers across West Java, the karinding is considered by many Sundanese to be their first musical instrument, and its sound is said to emulate the big bang. Its vibration and buzzing timbre are literally at the heart of Sundanese creation myths, and another example of how fundamental timbre is to the culture.

Despite this, the karinding, along with many other traditions, suffered during the political and social instability of the region during the twentieth century, and by the 1970s, it was in severe decline until it got picked up again in 2008 by the Ujungberung Rebels community.

They looked around at all the traditional Sundanese instruments and specifically chose the one that was the least popular and the most obscure. They intentionally chose the thing that was the most occult, in the sense of being hidden or unseen, overlooked, and buried.

They chose the most underdog instrument for this project specifically because they were the ultimate underdogs in that moment, and needed to rebuild their self image and rehabilitate their place in Bandung society. The karinding represented a way forward, as it was both completely original and totally Sundanese.

So this case study is about how Bandung metalheads bring metal aesthetics and approaches to traditional instruments, but it’s also about how the philosophy and metaphysics of the karinding are brought to bear on local variants of metal.

My doctoral research was all about the dynamics of jaw harp revivals, and the situation in Bandung mirrors other case studies in several regards. As pointed out by Caroline Bithell and Juniper Hill in the Oxford Handbook of Music Revival, “many revivals are driven by impassioned and committed individuals” (Bithell and Hill 2014, 10), referencing Antony Wallace’s “charismatic evangelists” and Ronström’s “burning souls” (ibid, 45).

Similarly, the karinding’s resurgence is largely due to the efforts of a very small group of people. Digging up forgotten traditions requires strong-willed advocates who are willing to go against the grain of mainstream tastes—and who better than metalheads to hold down that position?

In Bandung, Kimung, one of the original Rebels who contributed to the very DNA of Indonesian metal, turned out to be that person. Due largely to his efforts, karinding has transformed into a youth movement that’s still going today, even if there are now fewer karinding metal bands than there were 10 years ago.

A former teacher, Kimung founded the Kelas Karinding (literally karinding class), a free afterschool program teaching youth to play the instrument. He’s been facilitating this for many years, and the influence of his work and status in the community has gone a long way to re-establishing the instrument as part of daily Sundanese life.

Post-2008, there was an explosion of karinding bands inspired by Karinding Attack and Kelas Karinding. Many of these bands were formed by metalhead teenagers following in the footsteps of their elders from Ujungberung.

While the top handful of karinding metal bands are still active today, they’ve never seen the success of the death metal bands that birthed them, making them somewhat marginal even within the underground.

So, did heavy bamboo actually become a new genre, or was it more of a collaboration, like the boundaried cross-pollination between the metal scene and the reak trance scene in Bandung as discussed by Luigi Monteanni?

Not exactly. I argue that bamboo-core was more of a developmental phase. Not so much a genre as an artistic movement that opened doors to new opportunities.

This developmental phase in metal has propelled karinding onwards into other local environments. In addition to publishing several history books about the metal scene and the karinding, Kimung is now working at the Atap Foundation, a media centre that teaches youth film, animation, and music recording. He is now in a new stage of his “karinding campaign”, where he is not only influencing youth to embrace the instrument, but helping them develop a wider array of skills in order to make art about it and use it to tell more distinctly Sundanese stories.

He has acted as the producer of several animated films, documentaries, a karinding compilation album of different bands, and of course, his book The History of Karinding in Priangan (2019)—note the blackletter font on the book cover.

Finally, he has his sights set on integrating karinding into the mainstream, forming a karinding orchestra and spearheading a collaboration between that group and a Western-style orchestra, experimenting with different tunings in order to make the instrument playable with a wider array of instruments (including different styles of gamelan) and finally, working on an application to get the Sundanese karinding registered with UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Some may wonder if he has outgrown his metal roots, so it’s worth noting that he has done all of this using his same social media handle: @kimun666

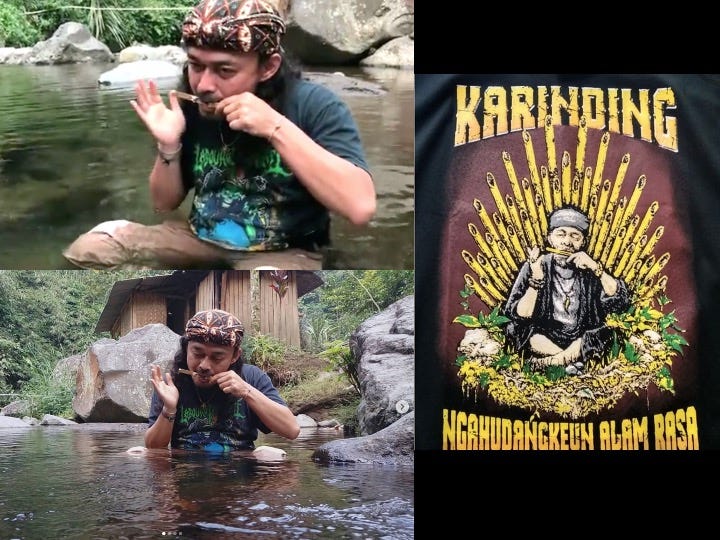

Kimung is not the only Rebel whose work with karinding has moved further afield. Man Jasad is now working as a cultural ambassador with the local government to preserve Sundanese arts in his region of West Java. Despite moving into local politics, like Kimung he still centers his identity as a metalhead, as you can see in this screenshot from an Instagram video of him playing karinding in a sacred spring while wearing a metal shirt.

He captioned the video with the same Sundanese phrase seen on the tshirt on the right, which translates as “awaken the senses”. Note the meditative pose and demeanour in both images. This echoes the sentiment that playing karinding, whether you’re a metalhead or not, is ultimately about reconnecting with yourself and finding an existential anchor, a throughline to a sense of self, history, and eternal present. And strong, connected selves are precisely what is required in order to refuse and resist the constant onslaught of hegemonic forces that are designed to separate us from who we are, in order to make us compliant and complicit in power structures that threaten our very survival.

Today I’ve shown how the Sundanese embrace of metal—not as something foreign but as something that already aesthetically and timbrally made sense—led to the revival of a local traditional instrument. Importantly, the karinding case is not folk metal, it’s a folk revival that has emerged from metal.

During the first keynote panel of the 2025 ISMMS conference in Seville, Nelson Varas-Diaz asked: what have we missed and overlooked in metal studies? This presentation suggests that the relationship between metal scenes and folk revivals could be one of those areas. Can we shift the frame to include not just the music that bands make but the impacts they have on their communities? How do bands who incorporate folk instruments influence the wider understanding of those traditions?

I’ll end by asking the audience, can you think of any other examples of folk revivals that have come out of a metal scene? I welcome your questions and comments!

Works Cited

Bithell, Caroline, and Juniper Hill, eds. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Groth, S. K., & Bubandt, N. (2024). Noise Without Noise: Art Interventions in a Southeast Asian City. In InterNoise 2024: Proceedings of the 53rd International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering: 1-11.

Kimung. 2019. Sejarah Karinding Priangan. Minor Books.

Kimung. 2022. The Dynamics of Karinding in West Java. Journal of the International Jew’s Harp Society 7: 22-33.

Monteanni, Luigi. 2025. “Extreme Traditions: On Bandung’s Intergenerational Sonic Ecologies.” CTM Festival Magazine. https://www.ctm-festival.de/magazine/extreme-traditions-on-bandungs-inter-generational-sonic-ecologies.

Monteanni, Luigi. 2025. “Extreme Traditions: On Bandung’s Intergenerational Sonic Ecologies.” CTM Festival Magazine. https://www.ctm-festival.de/magazine/extreme-traditions-on-bandungs-inter-generational-sonic-ecologies.

Spiller, Henry. 2023. Archaic Instruments in Modern West Java: Bamboo Murmurs. SOAS Studies in Music. New York: Routledge, 2023.